"If a PFM reform makes no difference in the life of a villager, then you’ve not succeeded.” So said Keith Muhakanizi, permanent secretary in the Ugandan Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, in remarks that set the tone for the two-day public financial management workshop facilitated by CABRI in Kampala, Uganda, on 18 and 19 August 2015.

Senior budget officials from Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, The Gambia, Uganda and Zanzibar participated in an interactive workshop format that tackled two central questions:

- Why do PFM reforms often not deliver on expected results?

- What will contribute to greater success?

The workshop programme covered four common PFM reform areas: the policy-budget link, procurement practices, integrated financial management systems, and accountability.

In each session CABRI used different facilitation techniques based on fictitious case studies that represented the challenges and complexities faced by budget officials. The workshop format encouraged frank and open self-reflection.

In this blog, the first in a two-part series, we examine the first two sessions: the policy-budget link, and procurement practices. In the next blog we will look at integrated financial management systems, and accountability for better services.

The policy-budget link

In the session on the policy-budget link, a graphic novel followed a budget reform superhero in his quest to introduce performance-based budgeting. But the implementation of this reform fell flat due to, among other reasons, lack of buy-in by stakeholders, the persistence of traditional practices, inappropriate reform processes and the limited capabilities put in place to implement the reform.

Participants examined why these challenges existed and discussed how to address them, using their own experiences as reference points.

Political leadership, the buy-in of affected actors, and building trust between actors, most possible in a reform process owned and led by government, were identified as necessary conditions.

To build this trust, participants noted that the finance ministry must change its budget process behaviour as well as its skill profile. It should also have a clear, shared framework of national priorities against which allocations are made, and a sound fiscal framework based on realistic revenue projections. Without these, budget decisions are too easily dominated by non-policy factors and expenditure ceilings lack credibility, resulting in broken links between budgets and policy.

Programme budgeting also requires officials across government to change the way they think, deliver and communicate. Creating opportunities for these officials’ early engagement in reforms, and a considered approach to building capabilities, are crucial. Finally, the participants emphasised that countries need to be sensitive to how their budget system reacts to reforms, and adapt their reform approach and pace accordingly.

Procurement practices

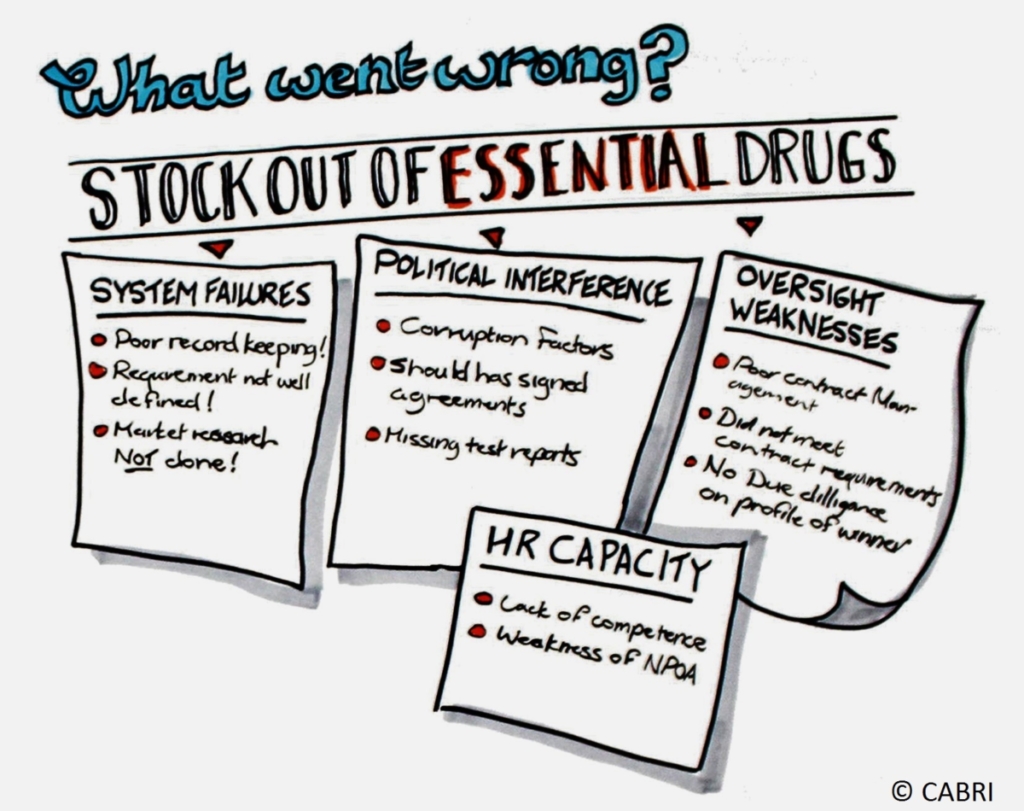

The common pitfalls of procurement reform were examined through a newspaper article on a drugs procurement scandal, which resulted in essential medical drugs not being delivered to primary clinics. Participants analysed the case against the necessary building blocks of an effective tender process.

They found that procurement reforms are often incomplete and poorly implemented. This results in a reformed system plagued by pre-reform problems. System failures (such as weak tender preparation, part or non-compliance, and weak record-keeping) are compounded by weak oversight, undermining value for money and creating space for political interference and corruption.

When identifying requirements to improve the implementation of procurement processes, participants highlighted the need for a high degree of standardisation (particularly when country procurement capacity is weak) and transparency, from planning to contract management.

Open procurement processes with civil society participation were discussed, and participants agreed that such openness will boost accountability, contributing to value for money, but also that not all steps lend themselves equally to openness.

Furthermore, participants emphasised the need for an oversight authority that is well equipped and independent in terms of its budget, its reporting obligations to stakeholders and the selection of its staff.

Note. The illustrations were drawn by Grant Johnson from Graphic Harvest to capture key points made during the workshop. This workshop was funded with UK aid from the British people.