Turning extractive resources (mining, oil and gas) into development outcomes has proven to be a challenge for African governments and developing countries in general. The channels linking minerals in the ground with higher living standards are complex. This article sets out some thoughts that the authors would like to share and also, initiatives taken by the African Development Bank and the Collaborative African Budget Reform Initiative (CABRI) to help African governments on the issue.

Managing risks

The first step for developing countries is to mitigate the economic risks presented by extractive resources. The finiteness of resources, and the volatility of commodity prices in global markets are threats to resource-rich countries. To avoid dangerous cliff-edges, they need to embed, in their budgetary policies and processes, mechanisms to protect spending programs from sudden drops in revenues. Governments also need to ensure that resource wealth is preserved for future generations after the actual resource in the ground is exhausted.

Second, extractive industries are capital intensive, utilizing complex machinery and advanced skills as inputs into the extraction process rather than a large workforce. Governments have to contend with the gap between citizens’ heightened expectations of economic opportunities and the limited amount of direct jobs created.

Third, government are often in an informational disadvantage vis-à-vis extractive companies, having limited knowledge of the value of mineral assets on the ground, the cost of extraction, the flow of revenues that can be expected to be generated and the impact of extraction on the surrounding communities. Asymmetric information reduces the effectiveness of government action and government’s capacity to design the fiscal and regulatory tools that can maximize the value of resources for its citizens.

Applying a policy framework

If the list of risks to manage is long, the opportunities to link mining, oil and gas to development outcomes are also complex and multilayered, as outlined in an analysis by the African Natural Resource Center of the African Development Bank. These opportunities include the “fiscal channel” where governments tax proceeds from extractives to invest them through the national budget, and direct channels which harness expenditure directly undertaken by extractive companies when running their operations – mostly by stimulating the participation of local companies in the supply and value chains of the extractive industries and by fostering skills and technology transfers. The importance of a comprehensive policy framework that comprises these channels was the topic of a policy workshop convened by CABRI in Accra in 2016, attended by policymakers from eight African governments.

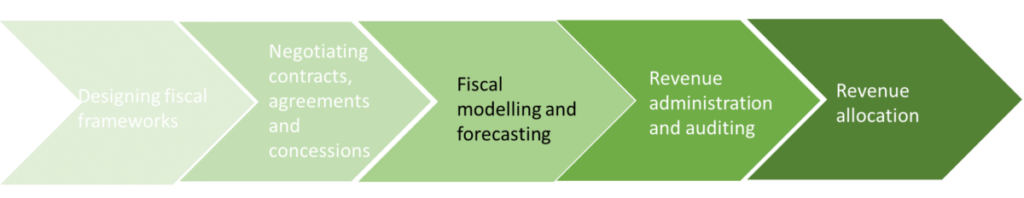

In order to implement this framework, African policymakers need to sharpen specific policy tools to support each step of the extractive resources policy cycle outlined in the figure below.

The extractive resources policy value chain

Reaching a good deal

Firstly, African countries need to appropriate a fair share of benefits from extractive resources. Mineral and petroleum deposits in Africa are usually owned by the nation but are extracted by commercial enterprises under contractual lease arrangements. In light of the experience of the African Legal Support Facility (ALSF), an international organization hosted by the African Development Bank which provides legal advice and technical assistance on complex transactions, African governments need to bridge informational and technical asymmetries when negotiating with international extractive companies.

Reaching a good deal with the private sector requires governments to have a clear vision of what they want to achieve out of their resource endowment. It is critical that governments have a clear roadmap of how to achieve a good deal prior to sitting at the negotiating table. African governments must ensure that the basic legal and regulatory framework is in place; and that their negotiating team has a broad composition reflecting the multifaceted skills required for a successful negotiation. Tools such as the African Mining Legislation Atlas, a free online resource for African mining legislation and regulation, and ResourceContracts.org, repository of publicly available investment contracts for oil, gas and mining projects have been designed with a view to benchmark regulatory and contractual approaches against experiences elsewhere, and help redress informational disadvantages.

Using financial models

Secondly, good policy making, including negotiation strategies, needs to be grounded in robust analytics and a sound understanding of the economic and fiscal impact of different options. Financial models, which are basically a linked system of variables where a user can change a range of inputs to see the impact it has on outputs, can help to:

- simulate the impact of changes in fiscal terms on extractive activities

- inform government’s negotiating position for resource contracts, leases and production sharing agreements

- inform tax collection by providing a baseline against which to assess actual revenue collected (“tax gap analysis”).

Extractive companies and investors use financial models intensively to assess the financial feasibility of projects under a range of technical, operational, market and regulatory scenarios. African governments are increasingly adopting financial models to guide decisions in managing extractive resources. A report of the African Development Bank, soon to be published, argues that a larger investment in capacity for financial modelling, and an approach that links the use of models to decision making across all phases of the policy value chain would greatly strengthen policy effectiveness.

Managing the revenues

Finally, revenue derived from the extractives sector, if managed well, has the potential to transform a country’s economy. In the past, many resource-dependent countries have exacerbated instabilities by implementing fiscal policies in a pro-cyclical manner, spending recklessly in boom periods and having to introduce severe austerity as prices trend downwards, which damages confidence and retards growth. The implications of extractive industries for Public Financial Management (PFM) practitioners start well before the onset of direct revenue accruing from the sale of resources. As such, public finances will be affected by various planning decisions that are made prior to the accrual of revenue, such as local content and industrial policy decisions.

Once revenues begin to flow, a critical early issue would be the decision regarding the balance between spending and saving. Policy-makers also need to find innovative ways of allocating expenditures that promote long-term fiscal sustainability, while avoiding the deterioration of the non-resource economy. Ideally, extractives revenue should be integrated within the existing PFM system to maintain the integrity of the budget process.

Upcoming Policy Workshop

These issues will be at the core of the discussion at a regional workshop to be hosted by the African Development Bank and CABRI, with the collaboration of the ALSF on 7 September in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, gathering senior officials from Ministries of Budget/Finance, Mining and Petroleum of five West African resource-rich countries to discuss negotiating strategies, modelling tools and policy frameworks to turn extractive resources into development outcomes.