The 2015 Open Budget Index was recently launched by the International Budget Partnership (IBP). The index is based on a budget transparency survey of more than 100 countries, including 31 African countries. The survey uses 109 indicators to assess which of the eight key budget documents a government makes available to the public, these being the: pre-budget statement; executive’s budget proposals; enacted budget; citizens budget, quarterly reports; mid-year reviews; year-end reports; and audit. Timeliness, comprehensiveness and usefulness are also measured. Based on the survey findings, a score of 0 to 100 and, depending on their score, participating countries are placed in one of 5 categories - scarce, minimal, some, significant and extensive information.

In our work with various African countries on improving budget transparency and participation, CABRI used the OBI as well as the ‘open budget tracker’ to observe the progress towards greater budget transparency. In 2013 and 2014, CABRI and the IBP undertook three separate transparency reviews in Kenya, DRC and Tunisia. For each of the reviews, government officials and representatives from civil society from the three countries, as well as peers from about 15 other African countries, participated in a process of identifying the challenges that impede transparency and participation and developed recommendations on ways that these can be overcome.

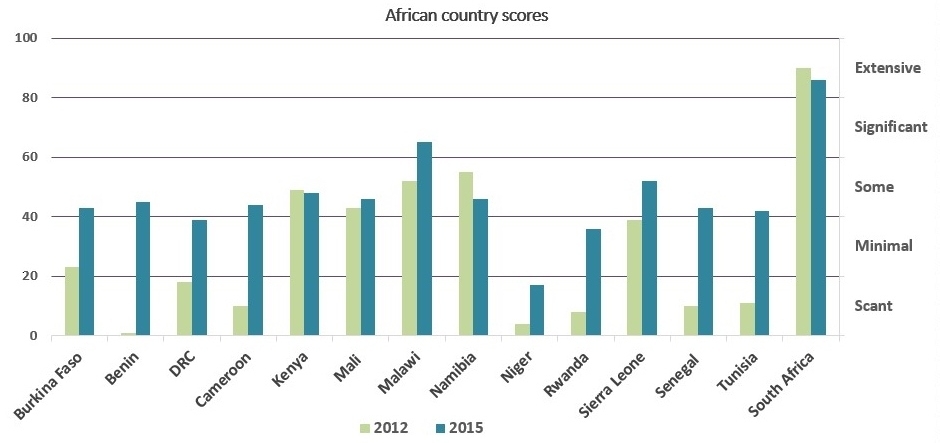

The stand out result from the 2015 index is that African countries have improved their transparency scores. From 2012 to 2015, African countries improved by an average of 9.4% in the index (compared to 3% from 2010 to 2012), with Tunisia, the DRC, Senegal, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Zambia and Benin posting the most impressive improvements. Looking at the trends since 2006, it would appear that countries find it relatively easy to improve their scores to “minimal” and “some” budget information and relatively challenging to break through to the categories of “significant” and “extensive”. As expected, it is easier for countries to publish information that they already produce internally, which doesn’t necessarily require additional resources but rather the right political framework. In the past, Tunisia was producing the Executive’s Budget Proposal for internal use only but did not make it available to the public. The improvement in their score from 11 to 42 is the result of the publication and improved comprehensiveness of the Executives Budget Proposal, publication of the Pre-Budget Statement and Mid-Year Review as well as an indication of a more open political environment following the popular overthrow of the Ben Ali regime.

However, transparency gains can be easily reversed when it rides on the momentum of a popular revolt and very little else - this was well noted during the transparency review in Tunisia. In the years following the spring revolution of 2011, there was strong support for transparency and greater citizen participation in the policy-making processes, but the formalization of good practices through laws and regulations was needed to ensure sustainable gains in budget transparency. In terms of participation, the review assessed in Tunisia opportunities for the public to engage in the budget process needed to be formalised. This led to the recommendation that a legal framework be put in place, regulating citizen participation as well as the way in which budget decisions are communicated and discussions framed throughout the entire budget process, between CSO’s, the National Assembly, the Supreme Audit Institution, and the Ministry of Finance. For instance, this entailed the creation of an office within the National Assembly, which would be responsible for ensuring regular and timely publication of parliamentary activities as well as the development of a dissemination strategy for published documents.

Over the coming period, CABRI will more strongly promote a shift from nominal transparency to active transparency. Although the OBI score provides an invaluable indication of a government’s commitment to budget openness, what matters in the end is the extent that greater transparency is able to: contribute to better policy choices; inform citizens’ dialogue and participation; expose non-delivery of public goods and services; and provide the relevant authorities with information to exercise their accountability powers. This is what we describe as active transparency.

Obviously, it is much easier to achieve nominal transparency, which may simply require the publishing of documents previously only available for internal use. Active transparency takes greater commitment and the appropriate technical capacity.